Feminist History at Leeds

Feminist History at Leeds

By Dr Jill Liddington, Honorary Research Fellow.

I am a feminist historian, inspired by Sheila Rowbotham’s pioneering text, Hidden from History (1973). I initially worked on the Votes for Women campaigns in Britain, especially across the north of England, all the while earning a living as a part-time adult education tutor. Then in 1982 I joined Leeds University’s Extramural Department (as it was then called), initially as a temporary half-time appointment. It drew me in and I worked there for over 20 years, teaching adult students, mainly off-campus. From 1990, I grew fascinated by the diaries of Anne Lister (1791-1840) of Shibden Hall, Halifax, transcribing and editing them; and at Leeds I eventually became a Reader in Gender History. Until the melancholy day in 2005 when the University decided to close down the School of Continuing Education (as we were then titled).

At this point, I had a new PhD student who wanted to research Votes for Women campaigns in Leeds. However I had no institutional base for our work. Where could she and I go? I lamented this to Ruth Holliday. And without hesitation she replied: ‘Come to CIGS’. And so I did. It became a happy home for my research. Earlier, I had taught on the Gender Studies degree course, and so was delighted to become an Honorary Research Fellow at CIGS.

Around 2003 I returned from Anne Lister back to Votes for Women campaigns, initially tracking the suffrage trail across the vast Yorkshire region. My research was enriched by the new digitalization of the 1901 census schedules. These documented the early lives of young suffragists and suffragettes just as the campaign was gaining momentum; and in 2006 Virago Press published Rebel Girls: their fight for the vote in 2006.

Later, after a Freedom of Information ruling, the 1911 census schedules were released two years early. With a fellow suffrage historian, I explored the nature and dimensions of the suffragette boycott of the Liberal Government’s household 1911 census, at the height of the Votes for Women campaigns. Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the Census was published in 2014 by Manchester University Press. With women over thirty winning the vote in 1918, the centenary loomed; so I was happily sucked into all the Votes 100 celebrations.

Then everything changed. My original Anne Lister book, Female Fortune: Land, Gender and Authority: the Anne Lister Diaries 1833-36, had been published back in 1998. It had garnered warm reviews. And in 2011, the diaries were recognized by UNESCO in its UK Memory of the World register, alongside that of Samuel Pepys. But beyond this, in the new century, serious interest in Anne Lister remained muted.

That is, until scriptwriter Sally Wainwright pitched her proposal for a major television drama series on Anne Lister to BBC1. This was quickly snapped up and before long attracted American interest (HBO). Series 1 of Gentleman Jack aired in spring 2019. Its impact was phenomenal.

Soon, a dynamic American woman, Pat Esgate, launched Anne Lister Birthday Weekend (ALBW). Hundreds of overseas visitors planned to arrive in Halifax at Easter. Everything Anne Lister now took over my life: talks, walks, tweets (though I was a latecomer to Twitter). That is, till March 2020 when the Covid lockdown changed all our lives drastically. Like so many others, I panicked, slashing through all the Anne Lister events in my diary. With no planes, all our plans had to be cancelled. Everything shut – except hospitals.

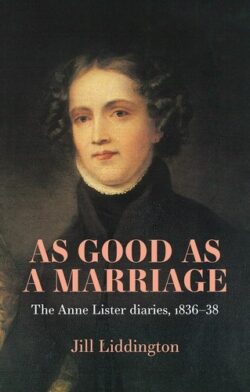

I’m a projects person. And I knew that to survive the lockdown, I needed a new research focus. It would have to be compelling Anne Lister. So I embarked on the sequel to Female Fortune. Manchester University Press had recently brought out a new edition of Female Fortune, and my MUP editor, Emma Brennan, was keenly interested. So now, with little to distract me from research and writing, I could work super-fast. And MUP published As Good As a Marriage: the Anne Lister diaries 1836-38 this spring. By which time, ALBW2023 had brought Americans and other visitors flocking to Halifax and Shibden Hall.

*

So what is so special about the Anne Lister diaries? First, their length. They start in 1806 when she was just fifteen and continue with scarce a gap till her death in Russia in 1840. Indeed, in 1984 the Guardian published an article on Anne Lister, its title was ‘The two million word enigma’. Until then, the diaries were little known beyond Halifax Antiquarian Society circles. However I was now fascinated, and in 1990went into West Yorkshire Archives Service (WYAS) in Halifax Library to check if the Guardian was correct (as it was notorious for misprints). I counted words per line, lines per page, pages per volume – and my calculations always came out at four million words. More recently, with the diaries now digitalized, and a WYAS Codebreakers volunteers’ project initiated, the word total is now thought to be nearer five million words. By comparison, Samuel Pepys’ diary (1660-69) is merely a million-and-a-quarter words. So Anne’s journals’ are four times the length of Pepys’.

Moreover, approximately one sixth of Anne’s diaries are written in her secret code. This she devised primarily to record her affairs, romantic and sexual, with other women. Eliza Raine, ‘a girl of colour’, had shared a room with Anne as pupils at the elite Manor boarding school in York. Later, her passionate affair with Mariana Lawton was frustrated by Mariana’s conventional marriage to an older wealthy landowner. Many other flirtations and affairs followed, in Yorkshire and in Paris. However, in 1832, with Anne thwarted by yet one more woman’s conventional marriage plans, she retreated morosely back to Shibden. Here she looked about for a life partner. Re-acquaintance with neighbouring heiress Ann Walker offered the perfect opportunity. Anne Lister wasted not a minute, deftly setting about wooing and seducing wealthy yet lonely Ann Walker. At Easter 1834, Anne and Ann took sacrament together at Goodramgate church in York, this ceremony privately sanctifying their marriage. And in the autumn, Ann Walker left her home and moved in to live at Shibden Hall with the Lister family.

Earlier, in 1826, Anne Lister had inherited Shibden Hall on the death of her uncle. And by late 1836, with the death of her elderly father and beloved aunt (plus departure of her irksome sister Marian) Anne and Anne lived on their own at Shibden, looked after by their growing number of servants. Now with access to Ann Walker’s considerable income stream, Anne could let rip her ambitious plans. Servants now included not only a groom but also a footman, both with appropriate livery. And Anne planned to glorify Shibden’s architecture with a grand tower, and to ensure her estate was as elegant as those of her elite friends.

As Good As a Marriage tracks in close and intimate details the two women’s lives together 1836-38. They enjoyed convivial evenings sharing the fireside in Shibden. Their relationship thrived when faced by a common enemy. At elections, as true ‘Blue’ landowners, they schemed energetically against the Whigs and – even worse – Radicals. (With no secret ballot yet, they could put effective political pressure on their enfranchised tenants. It mattered not that they could not vote themselves.) And they enjoyed travel away from Shibden. Indeed, they departed for France and the Pyrenees just as preparations for Queen Victoria’s Coronation were setting London abustle.

Yet the coded passages record tensions, silences and quarrels – with Ann Walker often in tears. perhaps fearing that Anne cared more about her Shibden legacy than for her. Yet how much liberty did conventionally married women enjoy in those pre-Victorian years, when legal rights of wives were still far away on the horizon?

Additional references

www.jliddington.org.uk for further details. Also:

Jill Liddington & Jill Norris, One Hand Tied Behind Us: the Rise of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, Virago 1978 (new editions 1984 and 2000; French edition, 2018).

Presenting the Past: Anne Lister of Halifax 1791-1840, 1994 and new edition 2010. This includes the melodramatic story of how Anne Lister’s secret code was eventually cracked at Shibden Hall late at night c.1892.